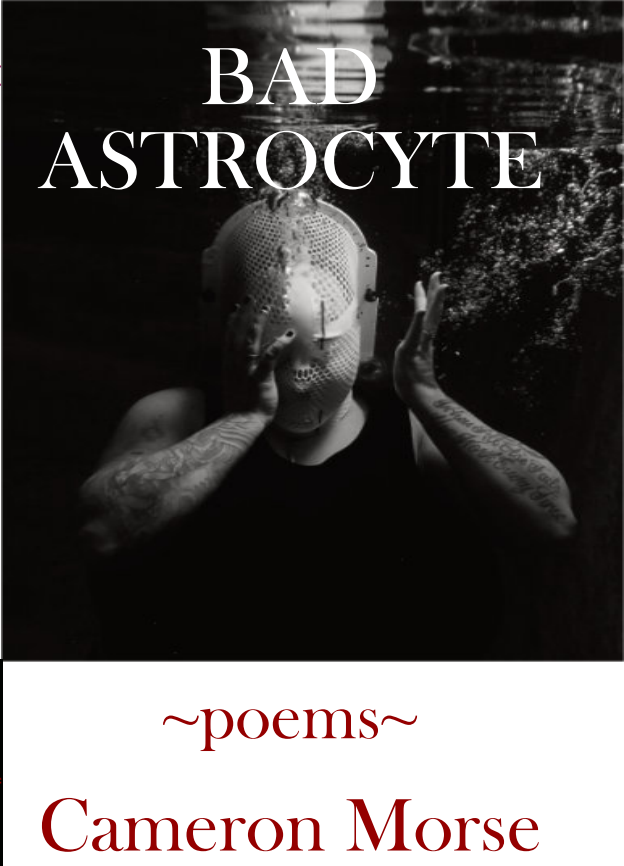

Bad Astrocyte

I can’t get enough of Cameron Morse’s poetry! Bad Astrocyte is dedicated “to the diagnosed,” but these poems also teach the undiagnosed about glioblastoma with a mix of facts, humor, and poignant honesty. Morse’s juxtapositions—a ruefully comical image of a toy car clogging a toilet followed by survival statistics followed by language like “I don’t obey my death order / I hibernate”—are constantly surprising. You’ll want to read this book again.

Katie Manning, author of Tasty Other

In Bad Astrocyte, Cameron Morse fires off lightning streaks in the form of elliptical threads that build and gather into something powerful and wholly real. What's left on the page is a processing mind, a mind breathing inward and outward, constantly recalibrating what it means to bring language into spaces where language so often resists entry: “Weight as yearning / as the waiting / room // Heavyhearted // the long wait / for word // of any kind” These poems show there is no such thing as silence and waiting and waste. If one is willing to listen long enough, be patient, be selective, there is only the glorious awareness of moments. And when moments are left in the hands of a poet like Morse, the mundane becomes extraordinary and the meditations on the unknown become akin to learning what it means to be alive.

--Jordan Stempleman, author of Wallop

In Bad Astrocyte, Cameron Morse asks, “Am I alive/ in this confection/ called cancer?” The disease does more than overshadow; it changes the poet’s consciousness, for “a cancer that begins/ in the brain/ becomes synonymous/ with the brain.” Little wonder, then, that although Morse minutely chronicles his survival he composes no straightforward patient narrative. Instead, the poet delivers incremental bits of anguish, anecdote, and clinical fact that crystalize into glittery verse fragments. The audience is invited to ponder not readymade or triumphant answers but unpunctuated phrases that fuse and collide, separated only by asterisks. Whether dishwashing or snow shoveling, Morse contemplates his significance on both a cosmic and a cellular level. He is a family man; he is a body full of chemicals. The effect is as disorienting as it is dazzling.

—L.S. Klatt, The Wilderness After Which